Creating ELA curriculum equity: The importance of culturally relevant books

By Alecia Mouhanna, Staff Writer | March 2021

When I was young, I loved the Little House on the Prairie series. As a child, I couldn’t get enough of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s tales of her 19th-century pioneer family as they traversed the country in search of a better future, persevering in the face of untold dangers and tragedies.

But a funny thing happened as I grew up. Revisiting the series through an older, more critical lens, I realized something: Laura was not simply the plucky prairie heroine I remembered. As an adult revisiting her books, I came to realize that her story and legacy were far more complex than I ever could have imagined at 8 years old – a realization underscored by the fact that in 2018, the Association for Library Service to Children, a division of the American Library Association, voted to remove her name from one of their annual children’s literature awards, citing the “anti-Native and anti-Black sentiments in her work”.

Is all of this to say that no one should ever read the Little House on the Prairie series again? Not necessarily – the Laura Ingalls Wilder Legacy and Research Association argues that “it is not beneficial to the body of literature to sweep away her name as though the perspectives in her books never existed. Those perspectives are teaching moments to show generations to come how the past was and how we, as a society, must move forward with a more inclusive and diverse perspective.”

But what this small anecdote does represent is a microcosm of why it’s so important for K-12 schools to prioritize adoption of inclusive, culturally relevant curriculum reading. Because the experience of one is not the experience of all, and yet for many students, their ELA reading occurs primarily through the narrative lens of white authors and white protagonists.

A matter of perspective: Why ELA inclusivity is important

When it comes to K-12 students – especially younger learners, who may not be able to assert agency over their reading options – the old adage is true: they only know what they know. And if their world is relatively insular and homogenous, then a context-free reading of texts that reinforce that perspective can be problematic. So they may end up espousing the view that Catcher in the Rye’s Holden Caulfield – a white, relatively wealthy teenage boy from the early 1950s – is an accurate, wholesale representation of a typical teenager, and not just one facet of the experience.

But what does this mean for underrepresented student groups – particularly students of color, who make up over half of U.S. public school enrollment – who may be looking at things from a much different perspective? What is their takeaway when their lessons are dominated by curriculum stalwarts centered on white characters? It might just be that their classroom reading doesn’t reflect their own lived experiences – making it difficult to engage with the texts. But it can also foster a long-term learning disconnect that does little to help reduce existing academic achievement gaps.

As journalist Amanda MacGregor notes in School Library Journal, “It’s not that Catcher is no longer worth picking up to read; it’s that in the nearly 70 years since this book’s publication, contemporary YA literature has flourished, offering teenagers reflections of all kinds of growing pains. When we challenge the classics, we make room for other texts, other voices, other experiences – ones more reflective of the teenagers reading them. Expanding the canon means centering and amplifying a wide range of voices.”

And a conscious effort to increase representation in K-12 schools has never been more necessary, particularly in the wake of 2020’s months-long global protests in support of the Black Lives Matter movement, sparked by the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, MN.

When it comes to curriculum overhaul, one size does not fit all

Outside of Common Core Standards (which have not been adopted by every U.S. state, and do not include a required reading list – though the exemplar texts do skew largely toward white authors), the U.S. does not have a centralized set of national education standards.

This means that curriculum updates can vary state-by-state, or even district by district, presenting a real challenge to any efforts toward widespread change. In many cases, it means that students are largely reading the same books, year after year – and have been, in some cases, for decades.

In the absence of concerted, unified efforts to introduce more diversity into ELA and other curriculum, some students and teachers have taken matters into their own hands. Grassroots organizations like student-led Diversify Our Narrative and educator-run #DisruptTexts were founded with a focus on campaigning for more equitable curricula, including (but not limited to) the addition of authors of color to required reading lists.

The challenges of building inclusive curriculum

Efforts to limit the outsized influence of classic texts in the classroom are often met with pushback, and not only because of the seemingly sacred space these books occupy in the literary canon. The longevity of these titles also means that educators typically have more lesson planning resources at their disposal, plus a higher level of comfort teaching them.

To illustrate this challenge, a nationally representative survey from EdWeek Research Center reported that while 83 percent of teachers said they were somewhat or very willing to teach an anti-racist curriculum, only 22 percent of nonwhite teachers and 9 percent of white teachers felt they had both the training and the resources to do so. Overcoming such a disparity will take more than a few new recommended or required reading lists – it will take a concerted effort on the part of teachers to look inward and learn, and on administrators to provide the necessary tools to facilitate that.

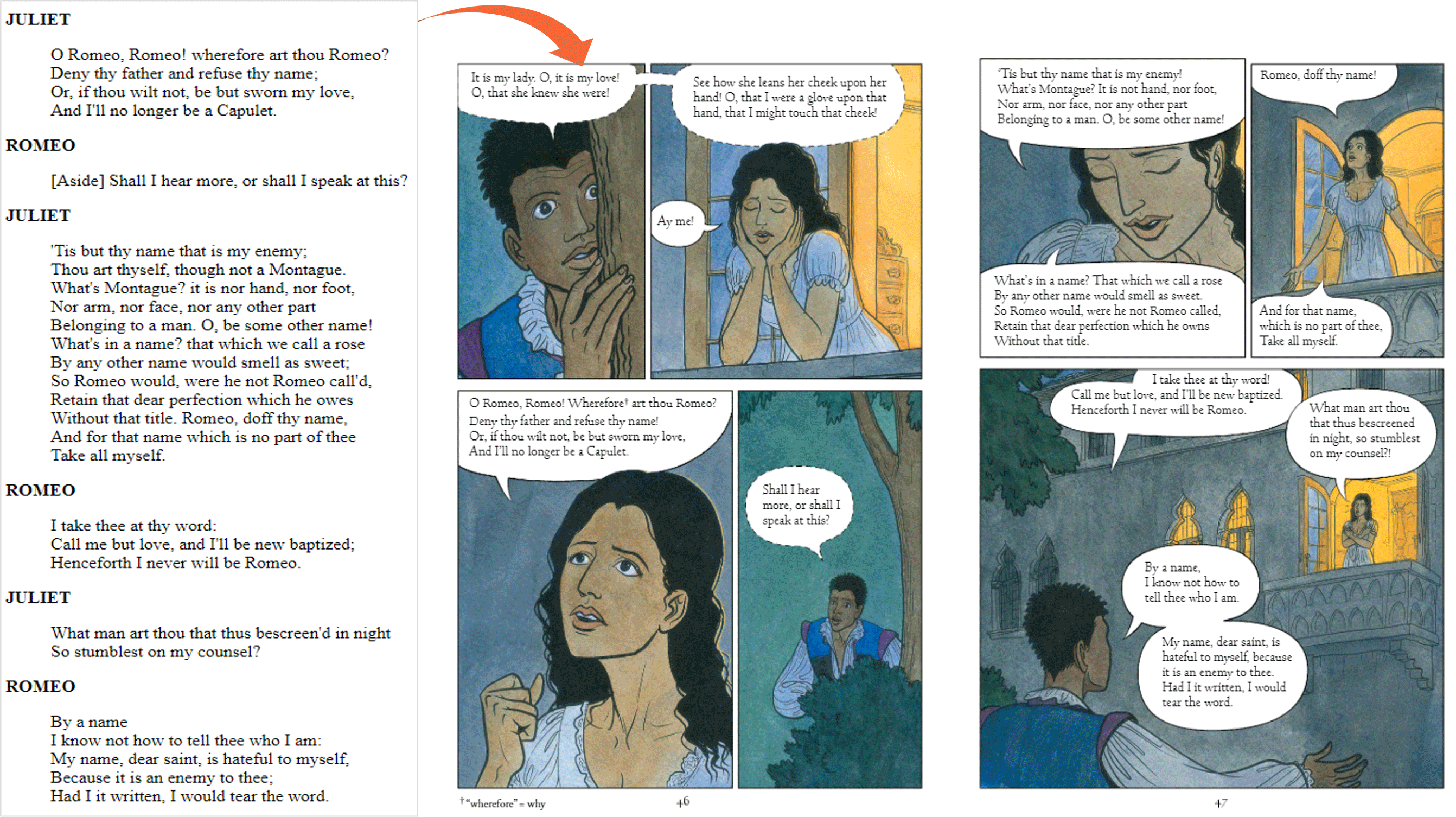

Unique adaptations of classic works of literature, like Gareth Hinds’ diversely cast graphic novelization of William Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet, enable educators to approach timeless stories from new, inclusive angles.

Unique adaptations of classic works of literature, like Gareth Hinds’ diversely cast graphic novelization of William Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet, enable educators to approach timeless stories from new, inclusive angles.Strategies to boost curriculum equity

Even taking the difficulties outlined above into consideration, there are smaller-scale steps that educators can take to begin integrating more representative reading into their lesson plans.

Here are a few strategies to consider implementing.

-

- Reframe seminal curriculum works by pairing them with inclusive contemporary texts that incorporate similar themes, but deliver them via alternate perspectives. Some popular companion texts to common books like Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird include contemporary titles like Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give or Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption.”

- Approach the classics from new angles, contextualizing problematic elements and finding fresh ways to deliver old stories. For example, Gareth Hinds’ graphic novelization of Romeo & Juliet features a diversely illustrated cast that underscores the play’s universal themes.

- First-grade teacher Keenan Lee recommends read-alouds as a way to incorporate culturally diverse texts into the classroom, featuring titles chosen by students and teachers.

- The founders behind #DisruptTexts suggest keeping these four pillars in mind to create a more equitable reading environment: 1.) Continuously interrogate biases to understand how they inform teaching; 2.) Center Black, Indigenous and voices of color and literature; 3.) Apply a critical literacy lens to teaching practices; and 4.) Work in community with others, especially BIPOC.

- Listen to your students – Often, students will be able to provide fresh insights and feedback on classroom reading based on their own unique experiences. By showing that their opinions are valued, educators can encourage more meaningful engagement with their learning overall.

Establishing a more equitable curriculum is not something that will happen overnight. But the results are well worth the time and effort, leading to a more comprehensive, inclusive learning experience that benefits all students and better prepares them for life in the real world.