Vox author Christina Dalcher examines the importance of language (Q&A)

By Jill Grunenwald, Staff Writer | November 2018

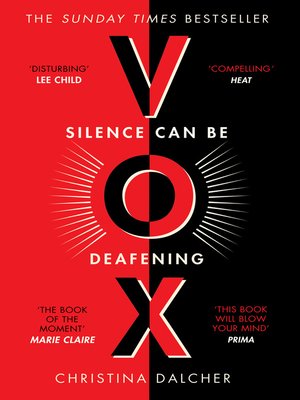

Imagine if you were limited to 100 words a day. How would you communicate with the people you love? This is the world envisioned by writer and linguist Christina Dalcher, whose 2018 dystopian thriller, Vox, examines a world in which women are systematically silenced. In its review, Publisher’s Weekly said Vox “carries an undeniably powerful message,” while Library Journal called it a “page-turning first novel.” Dalcher is also a writer of flash fiction (short, short stories) and previously taught undergraduate and post-graduate courses in linguistics, phonetics and phonology as well as writing and rhetoric. Perspectives on Reading was recently given an opportunity to speak with Dalcher about her book and the importance of language.

PoR: When I think about your book Vox, there is a Margaret Atwood quote I keep coming back to from The Robber Bride, which is “War is what happens when language fails.” In Vox, women are very limited in how many words they are allowed to use in a given day.

Christina Dalcher: Yes, extremely. From something like 16,000 [words per day] to 100, which is an extreme limitation.

PoR: What is it about language that made you want to write about it in such a way? Specifically the idea of limiting what we’re allowed to say. After all, using language is something that we all do all the time.

Christina Dalcher: Absolutely. And it’s something that we very much take for granted because we do it so well and so perfectly by the time we’re 3- or 4-years-old with no instruction. So if that’s taken away, what a shock that must be. Even women aside, we’re the only species that has language in a linguistic capacity. We’re not talking about communication, we’re talking about language, whether it’s signed or spoken. Dogs communicate, as do many other animals. But we’re the only ones that actually have language.

If we are limited in what we can say, obviously that doesn’t mean we’ve lost our linguistics capacity, but we are certainly silenced. And we’ve all been in situations where we’ve felt like we can’t say what we’re thinking for whatever reason, and I think it’s got to be quite horrible to push that to extremes. To really push that envelope and find ourselves in a situation where we want to express ourselves and we simply can’t. Obviously whoever is having her language limited is going to be at a severe disadvantage, so that’s one part of the answer.

The other part is what happens to this younger generation of girls if they’re not allowed to speak? I guess the question we have to ask is are they at risk of not even developing the kind of rich linguistics capacity that we all have grown up with and end up taking for granted? So, there are two answers: the smaller, more local answer and the more global answer, which would apply to the next generation in Vox.

PoR: As you said, there are situations where we sometimes censor ourselves. But of course there is a difference between self-censoring and being forced to censor yourself, which is what is happening in Vox. There are two generations here: the adult women who had previously lived in a world where they were not censored and they could say whatever they wanted and now are being censored; and the daughters who don’t know a world any different. To them this is just normal.

Christina Dalcher: Right. The power dynamics changed and even without talking about power for a moment, without talking about oppression, I have a very difficult time imagining not being able to carry on a conversation. It’s so important to me. My husband and I don’t watch a lot of television. We’re home together almost all of the time and our lives are one great, big, long conversation and so even putting the idea of oppression aside — obviously that’s definitely there when somebody is constrained not to speak — but even putting that aside, it’s really unfathomable for me to imagine even having a relationship without participating in this sort of ongoing marital conversation, or parent-child conversation or conversation between friends. So I think what that must do to a person psychologically I honestly can’t even begin to imagine it. It’s quite terrifying.

PoR: It really is, because we communicate through language and having that taken away, how do you learn to communicate with people when you don’t have language as an outlet for communication.

Christina Dalcher: Exactly, we’d end up being people spoken at, not necessarily to. I never got to this point in Vox, because while it is a thriller, we know from the first sentence that there is going to be a good outcome and the good guy is going to win. But while I was writing it, I was envisioning this future where a later generation of young daughters would be effectively pets.

Not even another human being in the household, because when you take away language, you’re really taking away something that is so endemic to our humanity and so unique to our humanity that it’s got to be dehumanizing. I cannot think of any other single thing that you could take away from people that would be so effective at dehumanizing them.

PoR: I know that there are studies about children who weren’t spoken to or don’t have language from a young age and how that lack of language affects them later. When you read about them, it’s so startling to find out what happens to these children and how they respond later in life after not having been exposed to language.

Christina Dalcher: The sad fact is that they don’t really respond because they have missed out on this critical period completely. It rarely happens, first of all. Linguists do not do experiments that involve language denial. However, every once in awhile the field comes across these feral children. The most recent case that has been most widely discussed, the one that’s mentioned in Vox and probably the one you know about, is Genie, the little girl in California who was severely abused and simply not socialized at all. For 13 1/2 years or more she was not spoken to or even at; she was denied language.

And as much as linguistics and psychologists worked for this little girl, they did not really see any results. She has been in a home living in complete anonymity ever since and there’s nothing we can do for her. It doesn’t happen very often, thankfully. When it does, the reason it is an opportunity for linguists is because they give us this insight into the notion of the “use it or lose it” stage, this critical period of acquisition. It’s not really a silver lining, but there does end up being some amount of benefit. It is absolutely terrifying and I cannot imagine what these people go through. And the only thing wrong with them is that they weren’t exposed to language and they couldn’t acquire it. What a crime that is.

PoR: Right, and again, it’s just something the rest of us take for granted. This ability to communicate.

Christina Dalcher: Absolutely. What I always try to ask people when I’m giving a little talk is how many people have actually taken a linguistics course and precious few have.

PoR: It’s funny, I actually did take a linguistics course in college.

Christina Dalcher: I am so happy to hear that!

PoR: My major was creative writing and as part of that and my English minor, I took a linguistics class and it really gave me a much greater appreciation for language in general, not just written, but the spoken portion of it. Studying the way your mouth moves for different sounds. Writing it is one thing, but the spoken language portion is a completely different thing that I had never encountered before. We would just be in class, manipulating our mouths in various ways to feel different sounds.

Christina Dalcher: That was my specialty when I taught, phonology and phonetic, and it was always very eye-opening. There would be these big “ah ha” moments when the students would have their mouths hanging open as if to say “I can do all of that?”

Now, of course, our technology has progressed and we are actually able to visualize the tongue as it moves with ultrasounds. And the gymnastics that this little guy does. It’s like having a ferret on steroids in your mouth. It’s unbelievable we do all of these things just in the course of a sentence.

If reading Vox makes one person say “I’m going to take a linguistics course,” I will be the happiest woman in the world.

PoR: Our magazine is all about reading, which is very dependent on language. As a linguist is there anything in particular about language that you would want people to know? That’s a very big question, I know.

Christina Dalcher: I think that probably the biggest thing that I would love people to take away, whether from reading Vox or from reading anything, is to stop for a moment and say, “Wow. This is what I can do? This is what my brain can do?” We have a finite set of words. Yes, we add a few words every year, but in general it’s a limited set, and we’ve also got a finite set of rules that govern how we can put these words together. From that finite set of words and finite set of rules we are able to create unique things. I’m going to guess if you go back into this interview and take any sentence of mine longer than 10 or 12 words, it is a sentence that has never been uttered before. It’s unique.

It’s mind-blowing, isn’t it? From a finite set of words and a finite set of rules, we are able to generate an infinite, infinite, infinite, I mean limitless number of sayings. I know you know what infinite means, but I’m so excited I have to keep saying that word over and over again. We can generate an infinite number of things.

And if we’re readers, we can comprehend those things that somebody else wrote. If we’re writers, we can generate them. If we’re thinking, we can think an infinite number of possibilities. This is how we get to building airplanes and things that fly to the moon and being able to talk about black holes.

That is limitless. That is such power. And we can do all of this stuff, obviously not as eloquently as when we are adults, but we can do all of this stuff when we’re kids, when we’re tiny little kids.

PoR: That really is mind-blowing.

Christina Dalcher: It is. And we still don’t really know how it works. That’s also kind of mind-blowing. We can teach computers how to play chess better than [Bobby] Fischer. We can program computers to wake us up according to our body’s natural rhythm. We can program computers to identify songs in seconds. But we still can’t really figure out how to teach a computer to do what every 3-year-old can do. That’s how magical language is.

Read a sample of Vox:

This interview has been condensed for length and lightly edited for clarity.