How are U.S. schools bridging the digital divide?

By Alecia Mouhanna, Staff Writer | September 2020

The U.S. education system is seemingly at a crossroads. With the coronavirus pandemic casting uncertainty over the future of in-classroom instruction, it’s clear that now more than ever, students need access to digital books and tools to have a chance at impactful learning. However, while we live in an increasingly digital age, many students lack that access.

The digital divide – also known as the “homework gap”– is a disparity that has been often discussed over the years but, in general, weakly addressed. And now, the pandemic has blown this societal fault line wide open.

The current state of the U.S. digital divide

According to the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) most recent Broadband Deployment Report, an estimated 18 million people lacked high-speed broadband internet access in 2020 – or, about 5 percent of the U.S. population. In context, this represents a decrease from 2019 estimates of 21.3 million people without broadband access. At face value, it might appear that the U.S. is closing the gap.

Chandra, S., Chang, A., Day, L., Fazlullah, A., Liu, J., McBride, L., Mudalige, T., Weiss, D., (2020). Closing the K–12 Digital Divide in the Age of Distance Learning. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media. Boston, Massachusetts, Boston Consulting Group.

Chandra, S., Chang, A., Day, L., Fazlullah, A., Liu, J., McBride, L., Mudalige, T., Weiss, D., (2020). Closing the K–12 Digital Divide in the Age of Distance Learning. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media. Boston, Massachusetts, Boston Consulting Group.However, these numbers may not necessarily tell the whole story. In the report’s dissent, Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel stridently disputes the FCC’s conclusions that the U.S. is making significant progress in efforts to extend broadband access to all U.S. citizens, asserting that the report’s methodology has resulted in a vast understatement of the true extent of the problem. According to Rosenworcel, if a broadband provider tells the FCC it can offer service to a single customer in a census block, that is sufficient for the agency to assume that service is available throughout the area. The FCC also lacks a system to independently verify the data, leading providers to frequently overstate service coverage in thousands of areas, sometimes by millions of people.

Furthermore, in a world where people spend more time than ever online, just having access to any internet connection may no longer be enough. Speed matters, too, and some say the FCC’s standard download metric of 25 megabits per second – a standard set in 2015 – is far too low to accurately measure adequate access in today’s highly plugged-in society.

Cost is another factor. Access does not always equal affordability, and many low- or fixed-income families rely on internet access via smartphone versus expensive at-home broadband, the former of which isn’t always as fast or reliable.

How the “homework gap” impacts student learning

So what does all of this mean for students? In sum, the digital divide makes it difficult (if not impossible) for some students to leverage the tools they need to effectively read and learn at home, whether during shorter breaks from in-classroom instruction or during longer periods of distance learning. Online tools like learning management systems, learning commons and video conferencing software have become critical to overcoming the challenges of delivering more seamless class-to-home instructional experiences to K-12 students.

However, the benefits of these tools are minimized if they can’t be leveraged properly. Without sufficient internet connectivity, students can’t download books, upload assignments or participate in video calls. And when they’re sharing devices, they may not be able to dedicate the screen time necessary to complete reading assignments or other homework.

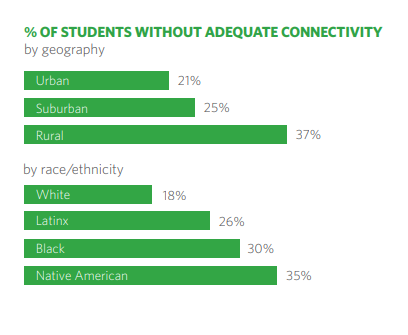

According to one report, up to 16 million students across all 50 U.S. states lack adequate access to the internet or devices in order to sustain effective at-home learning – and of that group, 9 million students lacked access to both, with rural students and students of color disproportionately impacted by this disparity. Per the report’s estimates, 37 percent of rural students lacked adequate access to the internet, compared to 21 percent of urban students and 25 percent of suburban students. By race, 30 percent of Black students, 26 percent of Latinx students and 35 percent of Native American students did not have sufficient connectivity, compared against 18 percent of white students.

In a normal year, these obstacles can lead to less favorable learning outcomes for disadvantaged students in comparison to their connected peers, including lower performance scores in reading, math and science. But in a year like 2020 – punctuated by pandemic-related school closures and a scrambled transition to distance learning – the long-term ramifications become even more apparent. By some estimates, students may lose up to seven months of academic progress in 2020 – and this number is no doubt much larger for students without home broadband and/or personal devices. Under such circumstances, instruction can become a never-ending game of catch-up.

Solving for the digital divide in schools and communities

In the absence of decisive federal action focused on closing the digital divide, much of the time it falls to state or local governments – or the school districts themselves – to provide short- and long-term solutions to the problem. For example:

-

- Several U.S. cities are pursuing plans to reclassify internet as a public utility. For example, in Cleveland, Ohio, the Cleveland Metropolitan School District is in talks with a local nonprofit to achieve this goal. Per current plans, CMSD would shoulder the monthly cost of the service, with the goal of connecting every district family to broadband service by the start of the 2022-2023 school year.

- In New Jersey – where as many as 230,000 students were left without needed devices and connectivity during closures – the state announced plans to target $54 million in federal funding to purchase Chromebooks, laptops and Wi-Fi hotspots to help fill statewide technology needs.

- The California Department of Education formed a statewide digital divide task force and fund to collect donations for devices for students. Thus far, the initiative has collected around 56,700 laptops and 94,000 hotspots distributed to districts across the state.

Some of these initiatives may provide a successful roadmap for other states, cities and school districts to follow suit. However, without focused federal intervention, it’s likely that efforts to close the digital divide will be unevenly applied, and it’s uncertain how far they’ll be able to go toward sparking impactful, long-term change.

What steps might the U.S. take at the national level to close the homework gap? Aside from new legislation, many educators are advocating for an expansion of the FCC’s E-Rate program, which provides around $4 billion annually toward discounts for telecommunications, internet access and internal connections to eligible schools and libraries. There are some who would like to see the program parameters extended to providing home broadband and device access to students and their families as well.

The future of the digital divide

Whether the digital divide is addressed ad hoc by state or school district, or wholesale at the federal level, it seems clear that inaction is no longer an option. Though digital books and tools certainly help bridge the gaps between school and home, students need to be assured steady, uninterrupted access to these resources for them to have the greatest possible impact.