Know your PAM score and improve population health

By Steve Potash, Publisher | September 2020

I volunteer on several committees at University Hospitals, a major metropolitan hospital system in Cleveland, Ohio. From my service there, I am learning about dramatic changes at the enterprise level as part of an ongoing transformation of the delivery of healthcare. This shift is driven by new “value-based payment models” that are replacing legacy service-based models. This industry-wide change impacts how healthcare providers are paid and costs reimbursed. What is measured is dependent on the quality of medical care delivered, versus the legacy system of payment for the number of procedures and services performed. The new systems are designed to promote better results in patient care delivered more efficiently while reducing costs. The overall goal is to create healthier populations.

Population health, defined

Population health, according to the Interdisciplinary Association for Population Health Science, is the “health of all people living in a given place,” such as Cleveland, Kansas or anywhere else in the world. Often, we think of health differences in terms of genetics or biology. But data proves that health needs and experiences go beyond gender or age. Where we live often predicts health outcomes, as does household income, level of education and literacy. Population health examines these disparities and seeks to provide healthcare providers with tools to improve outcomes in patient care and health management.

As part of the assessment of population health, data collected from patients along with data from their community inform value-based healthcare systems. This includes investing in personalized experiences, understanding the connection between workplace culture and population health, utilizing data to drive program design and a continued focus on private health information. An important tool used by the medical profession as part of providing a personalized healthcare experience is PAM, or Patient Activation Measure. A person’s PAM score has been proven to reliably assess the success of patient outcomes from a wide variety of situations. Here is how it works:

- The care provider asks the patient to take a short survey of 10 or more questions.

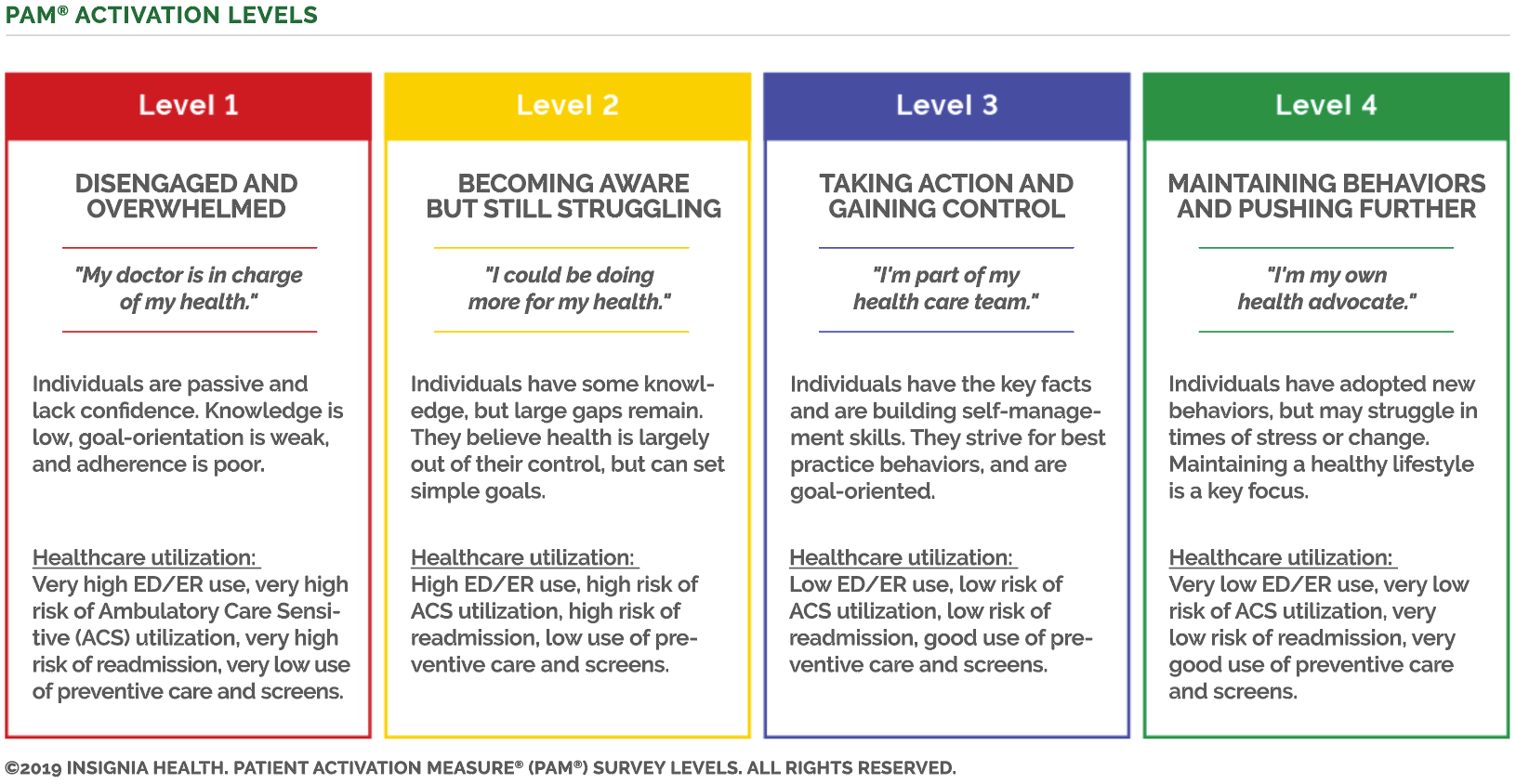

- The answers to the survey are scored and totaled. The total PAM score places the patient into one of four groups (levels 1-4). A PAM score at the lowest Level 1 indicates a disengaged and potentially overwhelmed patient who may be unlikely to adhere to recommended changes for their lifestyle and behavior. The top Level 4 indicates a highly engaged patient who will carefully follow medical guidance and modify their behavior as necessary.

Data shows patients with lower PAM scores are prone to poorer health outcomes than those with higher PAM scores. These include disease progressions, increased visits to the emergency room and other hospital admissions.

Healthy outcomes depend on patient literacy

We have become painfully aware as a result of COVID-19 that everyone can improve their own wellness (and that of their family and community) by following professional medical advice and guidance. While population health is proven to be dependent on PAM scores and patient behavior, it only follows that healthy outcomes are also highly dependent on patient literacy.

Literacy goes far beyond the ability to read a book. When it comes to healthcare, it’s about understanding a doctor, nurse or clinic’s written instruction. It also goes beyond the ability to read and comprehend just words. It requires the ability to understand numerical instructions, which are critical when patients are provided written instructions that describe the frequency and measurements for dosage of medicine or therapy treatments (e.g. 3 times for 20 min every 24 hours).

As I’ve discussed in a previous editorial, illiteracy and lack of numeracy are a reality for many people and can have life-threatening consequences. The Centers for Disease Control has found that “people with lower literacy proficiency are more likely than those with better literacy skills to report poor health.” So much of this is tied to health literacy and an individual’s ability to understand the information from their doctor. “Health literacy affects more than basic care instructions or how to take a medication. It determines a patient’s understanding about his or her health conditions, preventive treatments, compliance with treatment plans, health insurance options, informed consent and every aspect of the healthcare system,” says the Arkansas Foundation for Medical Care.

Improving health literacy

So how can we improve health literacy in our communities? I am proud to work alongside numerous educators, public and school librarians, and curriculum and literacy publishers that tackle this challenge. For every reader to achieve success with school, career and their own wellness, every person needs to have the content appropriate for their reading and comprehension skills. The medical profession in delivering health information can learn from decades of research on how books and curriculum are “leveled” to best match the reading abilities of students.

These methodologies provide great roadmaps for healthcare providers to consider how they level the information at every stage of interaction to adapt to the literacy level of the patient. Ideas for our health care providers, publishers, libraries and schools to consider to help improve population health include:

- Apply a variety of educational literacy methodologies for use in everyday healthcare instruction. These include literacy leveling, use of accessibility applications such as large print, digital content with dyslexic fonts, text to speech capabilities and built-in dictionaries. These literacy initiatives can be used for health information that is printed or otherwise delivered to the patient and the family, such as online or via recorded instructions.

- Apply tools from the edtech community to promote more active reader engagement and ways to measure and report when the patient accessed the content. K-12 schools report that students read more and are more engaged with the content when they are presented interactivity and opportunities to see their progress. We have first-hand success getting students to spend more time reading when they can earn achievement badges while using OverDrive’s Sora student reading app.

- The medical profession should leverage the proven experience of librarians, literacy experts and educators to review how they offer and deliver healthcare information that results in actual comprehension. Our nation’s schools and libraries are proven centers for excellence in adapting how readers can best benefit from information.

- Apply a series of “content level editions” for all information provided to those suffering from a particular illness or condition. Today, all patients are being provided the same written instructions and information. Programs that develop “adaptive” healthcare information need not only to account for the literacy level of the patient, the PAM score and who in the house is the best advocate for the patient.

As our society progresses toward value-based health systems, the topic of population health and health literacy are increasingly more important. As healthcare professionals continue to focus on patient-centered care and personalization of services, an emphasis on literacy and helping to raise everyone’s PAM score are part of the solution. Population health starts with population literacy.