The time for comics is NOW: Why comics are a powerful format in our age of distraction

By Shauna Darbyshire, Reference Associate | June 2019

My relationship with comics has developed and strengthened over the years. Like many 90s kids, I grew up with Archie, X-Men, Garfield, Charlie Brown, Spider-Man and Calvin & Hobbes. I then began delving into manga (Japanese comics) in my tween years. From these early reading explorations, I mainly associated comics with certain types of stories and characters: humorous, adventurous and larger-than-life. It wasn’t until I began working at the Wood Buffalo Regional Library (WBRL) in Fort McMurray, Alberta, eight years ago that I started to realize the true versatility of comics and how they are a format, not a genre.

Wednesday is the best day at WBRL; that’s when our new books come out, and over time I began to notice the diversity of the books being added to our graphic novel collection each week – they’re easily identifiable because of the red sticker on the spine. I was drawn to read more graphic novels – books that I might not have otherwise sought out had I not seen them amongst the new titles. My familiarity of the shelves of graphic novels at my library grew, surprising me with the growing variety of content available in comic format – informational comics, biographies and memoirs, humor, romance, horror, travel, and, yes, superheroes! I learned that “graphic novel” is essentially a fancified term for “comic;” while many standalone stories are published as “graphic novels,” often those slim, stapled paperback “comic” serials we buy at the comic store are later compiled into sturdier volumes of “graphic novels,” too. I began to notice in bookstores how there is a tendency to separate certain graphic novels out as being more or less “literary” than others despite the obvious subjectivity of such classification. I also noticed that the representation in many comics, especially newer ones, reflected the diversity of our world, including voices from individuals of different ages, abilities, ethnicities, cultures, sexualities and gender expressions.

A passion grew in me, and I felt the need to share the good word about comics far and wide, starting with our library patrons. One grandfatherly gentleman told me he thought he’d read just about every book on World War II in our library – imagine his surprise when I steered him into the graphic novel collection and showed him some wartime memoirs he’d never laid eyes on before.

I suggested a comic to a young girl who then told me, “I don’t like comics,” only to come back a week later and gush about how she enjoyed it so much that she used it for her school book report. I wondered, “Where did she get the notion that she didn’t like comics?” Interactions like these confirmed something that I had surmised – people would love comics if they only knew how versatile they really were and found a comic that was right for them.

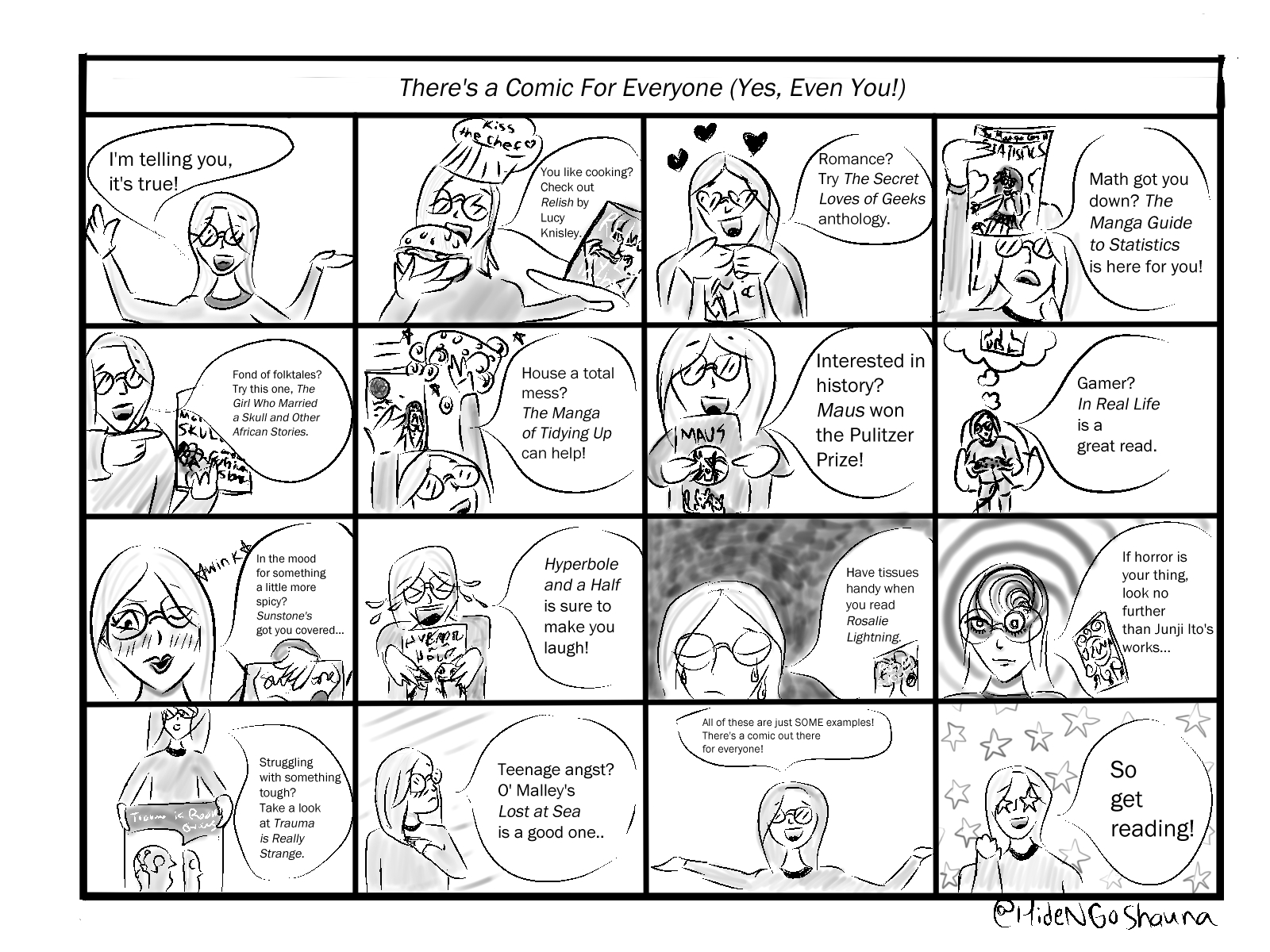

Armed with this insight, I became even more vocal about the power of comics, blogging, tweeting and submitting a presentation proposal about the versatility of comics for the Alberta Library Conference 2018. To my immense shock and surprise, my conference proposal was accepted, at which point I realized, “Holy hotcakes Batman, I’m going to Jasper to present in front of a room full of strangers!” The following months included much research into the comic format, as well as a lot of anxious and excited preparation for public speaking. My session, “There’s a Graphic Novel for Everyone (Yes, Even You!),” was fairly well-attended, and despite my sometimes-quavering voice, I enjoyed facilitating it – and I’d never enjoyed presenting anything before in my life! I realized then that making a choice to present on something you’re passionate about is much different than presenting on an assigned topic in a school class, and that I wanted to continue advocating for comics and graphic novels. I’ve since adapted my original presentation for a variety of audiences, including library tours, school classes and teacher groups. If my efforts enlighten even one person to the real value of comics, then I’m happy.

Unfortunately, comics still face a baseless stigma, with many, including some teachers and parents, looking down their noses at comics as being a somehow lesser format incapable of being “literary.” Even worse is when people won’t recognize comics as a format at all and misrepresent them as a genre of “kid’s stuff and superheroes” – that’s if they have preferences and opinions on reading to begin with, which isn’t always the case.

Lately, people are setting aside less time to sit down for some quality time with a book, or to scroll through an entire magazine article. In a previous edition of Perspectives on Reading, publisher Steve Potash addressed some sobering statistics which reveal what he calls a “reading epidemic.” On the other hand, we are inundated daily with information on a previously unparalleled scale, with both reputable sources and scammy clickbait vying for our attention and ad dollars. In this distracted age where bite-sized memes and bullet-list articles reign supreme, how can we bring the attention of the masses to important information, ideas and reading in general? While the pleasures and insights of perusing a full-length written article or conquering the final chapter of a fabulous novel cannot be replaced, the fact is that many potential readers are put off by these walls of text. If we want our ideas and creations to gain traction and spread to the widest audience possible, there is another format to consider… yup, you guessed it: comics.

Comics are a format for everyone: from the young girl toting around her worn copy of DogMan to the grandfather who is outraged at the latest political comic shared on his Facebook newsfeed. Generally speaking, the perceptions of the masses haven’t caught up with how far comics have come since the Golden Age of superheroes. Today, a diverse wealth of comics is being published, crowdfunded and shared online, and there’s something out there for readers of all interests and literacy levels: “Not only do comics kind of surpass boundaries of linguistics and global boundaries, but they also can cross boundaries created by class, education, and even age.” (Fransman, 2014)

The visual element of comics gives them an edge for capturing a reader’s attention and imagination. In their book Art Matters: Because Your Imagination Can Change the World, Chris Riddell adds his illustrations to the writings of Neil Gaiman, with powerful effect. In the introduction, Riddell notes: “when wise words have visuals added to them, they seem to travel further online, like paper aeroplanes catching an updraught.” (Riddell, 2018, para.1) Indeed, if one looks at the sorts of posts that go viral on social media, more often than not a striking image makes a connection with the viewer and pulls them into the entirety of the post. It’s one thing to say “plastic is killing our oceans” and quite another to show an image of a turtle suffocating on a plastic straw. Similarly, whether a short four-panel, a full-length graphic novel or anything in between, comics are a versatile and attention-grabbing vehicle for sharing stories, memories, ideas and information. The visual impact of comics makes them intensely shareable, enabling the potential for their widespread consumption. A look at sales figures shows that comic book and graphic novel sales are steadily increasing, reaching a new high in 2018. (Schedeen, 2019) Online, various webcomics are circulating widely for their relatable, debatable and otherwise shareable content, ranging from the sharp political commentary offered by The Nib to Nathan Pyle’s out-of-this-world yet heartwarmingly familiar Strange Planet alien comics.

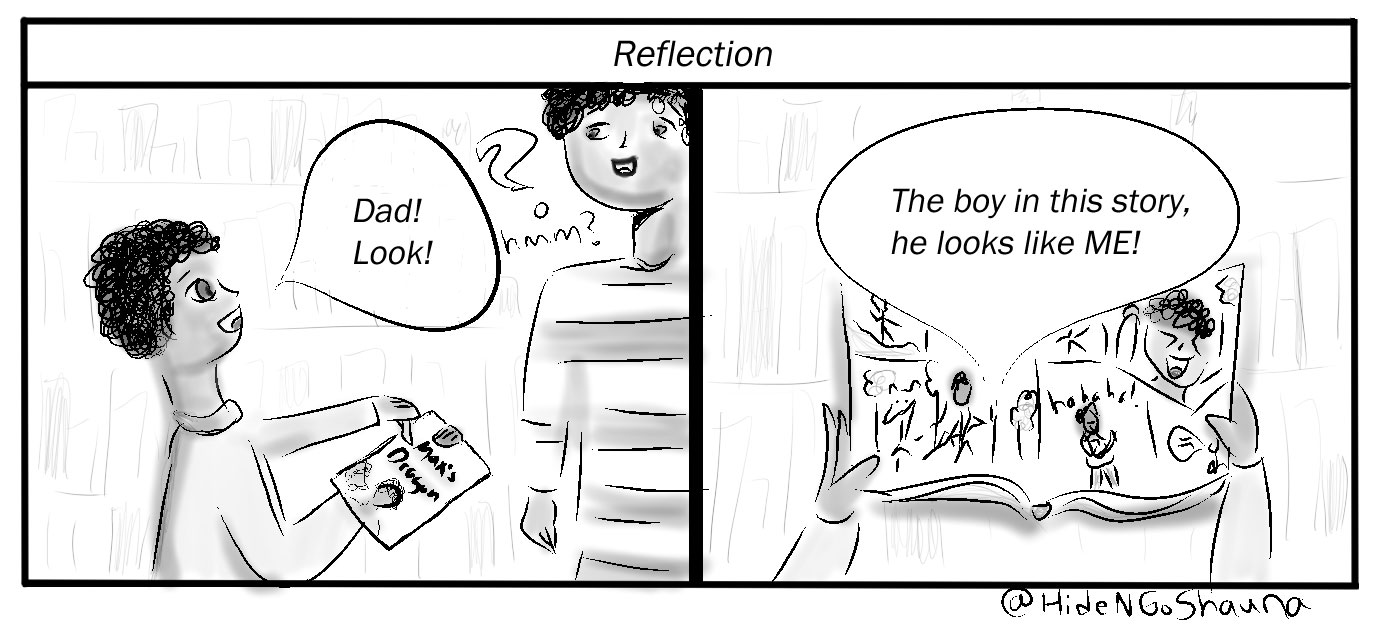

Speaking about what is widely shared online, one thing is endlessly true regardless of culture, age or one’s personal politics: people share things in which they see themselves reflected. Scrolling through a social media feed, you’re bound to come across popular memes like “only 90s kids could understand” or comments on funny videos such as “Wow! This is SOOO me! ???.” The visual nature of comics allows them to really support this yearning for representation among readers. While someone may pick up a novel and be unsure whether it will connect with them, it’s much easier to get a feel for a comic when you give it a quick flip through or even just a glance at the cover. With comics, the reader can feel a connection with a character instantaneously when they lay their eyes upon them, especially given the growing diversity of comics available today. In fact, the simplified reality of the sequential art in many comics can actually make them more relatable than more detailed renderings or photographs. As Scott McCloud explains in his game-changing work Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art: “The ability of cartoons to focus our attention on an idea is, I think, an important part of their special power… another is the universality of cartoon imagery. The more cartoony a face is, for instance, the more people it could be said to describe.” (p. 31)

Not only do comics reach us on a personal level, but they are also a powerful tool for social education and empathy building, as Erica Moen explained in an interview for the zine/blog Colouring Outside the Lines: “Images are a powerful form of communication. I’ve had several experiences with people telling me they are homophobic (not using that word, naturally), but after reading my comics they actually sympathized with queers for the first time or better understood the difficulties that queer people go through.” (2008) Furthermore, comics extend the invitation for us to take an intimate sensory look at unique and interesting aspects of other people’s cultures and develop an appreciation for them. Japanese manga, for example, has become a vital cultural export fostering a growing influx of manga-reading tourists to Japan, including myself.

The worldwide reach of comics in print and online is immense and awe-inspiring, but the impact of comics can also be felt closer to home, with homegrown efforts in local communities. Ever since I became the “comic girl” at my library, friends and colleagues have begun sending me articles about all sorts of comic-related news. Last year, the Alberta government began a project to create comics that will address alarming levels of Indigenous youth suicide (Wong, 2018). A woman in Calgary who experienced many micro-aggressions began a comic series that aims to combat racism and show others that they are not alone (Zoledziowski, 2018). A teacher in British Columbia recently created a thesis “someone might actually want to read” in comic form (Goodread, 2018). Today, the power of comics is more apparent than ever.

I’m working on my Master of Library and Information Studies through the University of Alberta. I’m currently completing a course on comics and graphic novels and loving every minute of it! I’m learning that I’m clearly not alone in my enthusiasm for comics, and that it’s an exciting time to be a creator or reader of comics. The stigma around comics is dissipating; there is no longer any question of their validity as a format. If someone is seeking a way to present an idea, share a story or bring attention to a cause, comics might be just the thing!

References

- Colouring Outside the Lines. (2008, July 19). Erika Moen interview. Retrieved from http://cotlzine.blogspot.com/2008/07/erika-moen-interview.html

- Fransman, K. (2014, December 04). Why We Should Be Taking Comics More Seriously. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mA1vshSuyQU&t=1s

- Gaiman, N., & Riddell, C. (2018). Art Matters: Because Your Imagination Can Change the World. London: Headline.

- Goodyear, S. (2018, June 12). B.C. art teacher submits thesis in the form of a comic book | CBC Radio. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/radio/asithappens/as-it-happens-monday-edition-1.4700930/b-c-art-teacher-submits-thesis-in-the-form-of-a-comic-book-1.4700932

- McCloud, S. (1994). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. NY: HarperCollins.

- The Nib: Political cartoons and non-fiction comics. (2017, October 31). Retrieved from https://thenib.com/

- Potash, S. (2019, April 02). Editorial: Up in the sky…It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s a…book? Why we need reading heroes. Retrieved from https://perspectivesonreading.com/reading-heroes/

- Pyle, N. (n.d.). Strange Planet. Retrieved from https://www.nathanwpyle.art/strangeplanet

- Schedeen, J. (2019, May 06). Comic Book and Graphic Novel Sales Reached New High in 2018. Retrieved from https://ca.ign.com/articles/2019/05/06/comic-book-and-graphic-novel-sales-reached-new-high-in-2018

- Wong, J. (2018, April 13). Alberta government developing suicide prevention comic books for Indigenous youth. Retrieved from https://globalnews.ca/news/4142806/alberta-government-developing-suicide-prevention-comic-books-for-indigenous-youth/

- Zoledziowski, A. (2018, September 13). Calgary millennial using her comic book powers to combat racism. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/calgary/2018/09/13/calgary-millennial-using-her-comic-book-powers-to-combat-racism.html

Printed images — and the comic book medium’s unique presentation of them — are at the heart of this feature. We have set out to trace the evolution of American comics by looking at 100 pages that altered the course of the field’s history. We chose to focus on individual pages rather than complete works, single panels, or specific narrative moments because the page is the fundamental unit of a comic book. It is where multiple images can allow your eye to play around in time and space simultaneously, or where a single, full-page image can instantly sear itself into your brain. If there are words, they become elements of the image itself, thanks to the carefully chosen economy of the writer and the thoughtful graphic design of the letterer. In the best pages, one is torn between staring endlessly at what’s in front of you or excitedly turning to the next one to see where the story is going. When comics have moved in new directions, the pivot points come in a page.